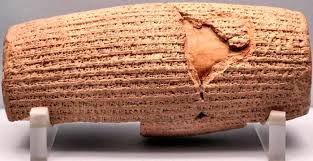

A 2,500-year-old cuneiform document ceremoniously displayed in a glass case at the United Nations in New York is revered as an “ancient declaration of human rights.” But in fact, argue researchers, the document was the work of a despot who had his enemies tortured.

Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi was planning a record-breaking gala. First he proclaimed the “White Revolution,” a land reform program, and then declared himself the “Light of the Aryans.” Finally, in October of 1971, he had taken it upon himself to celebrate “2,500 years of the Iranian monarchy.” The organizers of the celebration had promised to deliver “the greatest show on earth.”

Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi was planning a record-breaking gala. First he proclaimed the “White Revolution,” a land reform program, and then declared himself the “Light of the Aryans.” Finally, in October of 1971, he had taken it upon himself to celebrate “2,500 years of the Iranian monarchy.” The organizers of the celebration had promised to deliver “the greatest show on earth.”

The Shah had 50 opulent tents set up amid the ruins of Persepolis. Invited dignitaries included 69 heads of state and crowned monarchs. The guests consumed 20,000 liters of wine, ate quail eggs with pheasant and gilded caviar. Magnum bottles of Château Lafite circled the tables.

At the high point of the festival, the Shah walked to the grave of Cyrus II who, in the 6th century B.C., had conquered more than 5 million square kilometers (1.9 million square miles) of land in a long and bloody war.

Critics at the time complained that $100 million (€63 million) was a lot of money to spend celebrating the ancient Persian king. “Should I serve heads of state bread and radishes instead?” was the Shah’s brusque rejoinder.

Religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini, still in exile at the time, was also quick to issue his scathing criticism: “The crimes committed by Iranian kings have blackened the pages of history books.”

But the Shah knew better. Cyrus, he announced, was a very special man: noble and filled with love and kindness. The Shah insisted that Cyrus was the first to establish a right to “freedom of opinion.”^

‘Ancient Declaration of Human Rights’

Pahlevi also ensured that his view of history would be taken to the United Nations. On Oct. 14, just as the party in Persepolis was in full swing, his twin sister walked into the United Nations building in New York, where she handed a copy of a cuneiform document, about the size of a rolling pin, to then Secretary General Sithu U Thant. Thant thanked her for the “historic gift” and promptly praised it as an “ancient declaration of human rights.”

Suddenly even the UN secretary-general was insisting that Cyrus “wanted peace,” and that the Persian king had “shown the wisdom to respect other civilizations.”

Then Thant had the clay cylinder (which contains a supposedly particularly humane decree by Cyrus II dated 539 B.C.) displayed in a glass case in the main UN building. And there it continues to lie today, directly adjacent to a copy of the world’s oldest peace treaty.

Those were grand gestures and grand words, but in the end it was nothing but a hoax that the UN had fallen for. Contrary to the Shah’s claims, the cuneiform degree was “propaganda,” explains Josef Wiesehöfer, a scholar of ancient history at the University of Kiel in the northern Germany. “The notion that Cyrus introduced concepts of human rights is nonsense.”

Hanspeter Schaudig, an Assyriologist at the University of Heidelberg in the southwestern Germany, says that he too would be hard-pressed to see the ancient king as a pioneer when it comes to equality and human dignity. Indeed, Cyrus demanded that his subjects kiss his feet.

The ruler was responsible for a 30-year war that consumed the Orient and forced millions to pay heavy taxes. Anyone who refused stood to have his nose and ears cut off. Those sentenced to death were buried up to their heads in sand, left to be finished off by the sun.

Did the UN simply believe this historical lie — concocted by the Shah — without any further examination?

‘The UN Made a Serious Mistake’

Art historian Klaus Gallas, who is preparing a German-Iranian cultural festival to take place in Weimar next summer, has now brought the matter to the public’s attention. During his preparations for the festival he discovered the inconsistencies between the Shah’s claims and the Cyrus decree. “The UN made a serious mistake,” says Gallas.

The limestone tomb at Pasargadae of King Cyrus the Great.

Despite having been contacted by SPIEGEL several times, the organization has declined to comment on the incident. Indeed, the UN Information Service in Vienna continues to insist that many still consider the cuneiform cylinder from the Orient to be the “first human rights document.”

The aftermath of the hoax has been disastrous. Even German schoolbooks describe the ancient Persian king as a pioneer of humane policies. According to a forged translation on the Internet, Cyrus even supported a minimum wage and right to asylum.

“Slavery must be abolished throughout the world,” the fake translation reads. “Every country shall decide for itself whether or not it wants my leadership.”

Even Shirin Ebadi, the 2003 winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, was taken in by the hoax. “I am an Iranian. A descendant of Cyrus the Great,” she said in her speech in Oslo. “The very emperor who proclaimed at the pinnacle of power 2,500 years ago that … he would not reign over the people if they did not wish it.”

The experts are now stunned at this example of a rumor gone wild.

If one thing is clear, it is that the figure at the center of this hoax radically shook the ancient Orient like no other ruler. With what German scholar Wiesehöfer calls “military strokes of genius,” Cyrus advanced with his armies to India and to the Egyptian border. He is considered the creator of a new kind of country. At the height of his power, he was the ruler of a magnificent empire bursting with prosperity.

But it all began far more modestly. Born the son of an insignificant minor king in what is today southwestern Iran, the young man mounted the throne in 559 B.C.

Even in antiquity, bizarre legends were associated with the king. According to one of them, Cyrus grew up in the wild and was nursed by a female dog. There are no contemporary images of him.

His neighbors to the west soon felt the brunt of this man’s determination. After conquering the neighboring Elamite people, he attacked the Median Empire in 550 B.C. with his army’s fast combat chariots and soldiers dressed in bronze armor.

After that, the upstart king invaded Asia Minor, or modern Turkey, where hundreds of thousands of Greeks lived in colonies. Well-to-do citizens from Priene were enslaved.

‘One of the Most Magnificent Documents Ever Written’

The general recuperated from the trials of war at his residence in Pasargadae. It was surrounded by an irrigated garden known as the “paradeisos” and was home to a sumptuous harem.

But Cyrus soon became restless in his palace and returned to the front, this time heading east to Afghanistan. His life ended at 71, somewhere in Uzbekistan, when a spear punctured his thigh. He died three days later.

Courageous in battle and adept in the politics of running his empire, Cyrus, says Wiesehöfer, was a “pragmatist” who attained his goals with “carrots and sticks.” But he was no humanist.

Some Greeks praised the conqueror. Herodotus and Aeschylus (who lived after Cyrus’s death) called him merciful. The Bible describes him as the “anointed one,” because he supposedly permitted the abducted Jews to return to Israel.

But modern historians have long since debunked such reports as flattery. “A shining image of Cyrus was created in antiquity,” Wiesehöfer says. In truth, he was a violent ruler, like many others. His army ransacked residential neighborhoods and holy sites, and the urban elites were deported.

Only the Shah, who had his own problems in the 1960s, could have come up with the idea of reinterpreting this man as an originator of human rights. Despite his SAVAK secret police’s notorious torture practices, there was resistance throughout the country. Marxist groups carried out bombings while mullahs called upon their followers to resist the government.

In response, the Shah attempted to invoke his ancient predecessors. Just as Cyrus was once the father of the nation, he insisted, “So am I today.”

“The history of our empire begins with the famous proclamation by Cyrus,” the Shah claimed. “It is one of the most magnificent documents ever written on the spirit of freedom and justice in the history of mankind.”

One thing is true, and that is the clay cylinder documents a banal story of political betrayal. When the text was written in 539 B.C., Cyrus found himself in what was probably the most dramatic part of his life. He had dared to attack the New Babylonian Empire, his powerful rival for dominance of the Orient, a realm that extended all the way to Palestine. Its capital, the magnificent city of Babylon, crowned by a 91-meter tower, was also a center of knowledge and culture. The empire itself was bristling with weapons.

Nevertheless, the Persian ruler decided to risk attacking the Babylonians. His troops marched down the Tigris River. After attacking the fortified city of Opis and killing all prisoners, they advanced on Babylon.

Babylonian Betrayal

There, barricaded behind an 18-kilometer (11-mile) wall around the city, sat Cyrus’ beleaguered enemy: King Nabonid, an old man of 80.

At that very moment, the priests of the god Marduk were committing treason against their own country. Angry over the loss of power they had suffered under their king, they secretly opened the gates and allowed hostile Persian negotiators to enter the city. Nabonid was banished and his son murdered.

The conditions for a complete surrender were then hammered out. Cyrus demanded the release of fellow Persians who had been carried off in earlier wars. He also insisted on the return of stolen statues of gods.

These were the passages that the Shah would later reinterpret as a general rejection of slavery. In truth, Cyrus merely freed his own followers.

In compensation for their treacherous services, the priests were given money and estates. In return, they praised Cyrus as a “great” and “just” man and as someone who “saved the entire world from hardship and distress.”

Only after all the arrangements had been made did the king enter Babylon, riding in through the blue-glazed Gate of Ishtar. Reeds were spread on the ground at his feet. Then, as is written in line 19 of the Cyrus proclamation, the people were permitted to “kiss his feet.”

There is no evidence of moral reforms or humane commandments in the cuneiform document. Assyriologist Schaudig calls it “a brilliant piece of propaganda.”

But the legend of this prince of peace had been born, thanks to the wily priests of Babylon. And since it was placed on a pedestal by the UN, it has become even more inflated.

Iran’s mullahs have not escaped the Cyrus cult. In mid-June, the British Museum in London announced that it planned to lend the valuable original cylinder to Tehran. It has become an object of Persian national pride.

“The German Bundestag even recently received a petition to have the proclamation exhibited in a glass case at the Reichstag building,” says Gallas.

The petition was denied, and yet the distortion of history continues. With its disastrous tribute, the UN gave birth to a seemingly never-ending rumor.

As the saying from the Orient goes: “A fool may throw a stone into a well which a hundred wise men cannot pull out.”